|

THE TRUE PRICE OF COAL.

MOSS COLLIERY DISASTER OF 1871

Ince-in-Makerfield, was also the place of the Moss colliery disaster of 1871, it stands astride the A577, about a mile from Wigan. The pit was a relatively new one having only been opened a few years previously, and was worked by Messrs. Pearson and Knowles. The shafts here were sunk to a depth of some 580 yards where they intercepted the Cannel Seam. Work was going on in the upcast shaft by way of further sinking to reach the Arley Seam lower down. Although most of the mining took place in the Cannel Mine, some 12 months previous development was started in the Wigan Nine Feet.

This seam of coal lay at 480 yards down the shafts, and the workings at the time of the disaster only extended some 270 yards from the shaft. Near the mouthing of the Four Foot Seam, a short distance above the Wigan Nine Foot Seam was placed a ventilation furnace, this being the upcast shaft where further sinking was going on some 100 yards below.

The pit was considered to be adequately ventilated, indeed one of the underlookers a man named Prescott, stated that when he left the Nine Feet to go up to the ventilation furnace just five minutes before it fired that "A man might have gone through with a lighted torch with out danger". The day was Wednesday the 6th of September 1871. Down the pit were 68 men and boys at work in the nine feet seam and nearly the same number in the Cannel Mine. In addition there were six shaft sinkers at work in the upcast shaft. Just before eleven o'clock, three miners stepped into the cage at the upcast shaft to descend the mine. They were about halfway down the pit when the mine fired. From the upcast shaft, a thick plume of dense smoke rose into the air.

Shawled women with anxious faces waited for news of their loved ones, children stared wide eyed clutching their mothers dress, all waiting. The Government Inspector of Mines, was in Wigan at the time, and he too was soon at the scene. So too was Mr. Pickard the miners agent, he lived at Ince and was one of the first to arrive. The shafts were inspected and found to be badly damaged, the cage at the downcast had been thrown from its position. Nearby was found a cloth cap, this it was presumed, belonged to one of the miners that was descending the pit when the explosion occurred. As can be imagined, great anxiety was now being expressed for those below. After one and a half hours, a repair was made to the winding engine at the downcast shaft, and a hoppet was placed on the end of the rope. This was lowered into the mine, several minutes later it was raised...empty. Again the hoppet was lowered in the hope that anyone still living might be able to ascend; again it came up empty.

As is common in these cases, there is never any lack of volunteers, three men were lowered in the hoppet cautiously down as far as the Cannel mine. They returned to the joy of the crowds, with five colliers who announced that all the men in that seam were safe. The hoppet was lowered and raised in quick succession in order to get these men out before the oncome of the after-damp, and within a few hours all were out. An exploration party consisting of Mr. J. Bryham, Mr. Pickard the miners agent, Mr. Carter the underground manager and Mr. W. Hampson descended the upcast shaft. They stopped first at the Four Foot Seam, where the ventilation furnace was placed to check on the condition of the workings there. No-one it was surmised was working there, yet at the mouthing were three men, Henry Prescott, the underlooker, the furnace man and a brick setter all alive. They were quickly conveyed up the shaft, and a further attempt was made for the descent to the Nine Feet Seam. On arrival, the men in the hoppet were met by a group of colliers dreadfully injured and crying out for water and medical attention, some were beyond help.

The scene presented one of dereliction and destruction, timbers and roof supports were scattered about, coal tubs were bent and broken, the air was thick with a sulphurous smog. As many of the men that could be found alive were quickly sent up the shaft, tea and other refreshment were sent down on the return journey for the sufferers. Mr. Pickard was exploring the further workings, and ascended up the shaft about two o'clock. He reported that the sides of the pit were on fire, and preparations for a number of hand held extinguishers were arranged to be sent for. A party led by J. Bryham descended again into the pit in an attempt to quell the underground fires. Around twenty past three, the column of smoke from the upcast shaft ceased for a few seconds, followed by a low booming noise. Another explosion had occurred, not as great as the first but still caused great concern for the safety of the exploring parties still below ground. The hoppet was swiftly raised and out stepped Mr. Bryham and a number of rescuers, the others quickly followed, none were injured though some had been thrown about by the draught from the explosion, which took place in some other workings.

A consultation followed between the officials, who concluded that further explorations would be useless, there could be little doubt now as to the fate of the men still in the mine. To add further risk to the men attempting a rescue did not warrant further consideration, it was decided to seal the pits and block of the air to the fires underground. Twenty five colliers, thirty three drawers, six shaft sinkers, one fireman, two hookers-on, one winder-up, one of the men brought out of the Nine Feet workings had since died from his injuries, and the banksman. Seventy all told, and the wrath of the Moss Colliery disaster was not finished, as we shall see. The road to Moss Colliery, and the pit bank itself was covered in a mass of bereaved and distressed relatives and friends, the feeling of utter despair that only mining communities can share. Women whose husbands worked in the neighbouring collieries, came to give their support for they knew in their hearts that colliery explosions have no friends. Tomorrow it may be they who are mourning. By Thursday night both shafts at the colliery were covered over with brickwork, and puddled with clay to deprive the underground fires of oxygen.

It was not until Wednesday 20th of September, two weeks after the initial explosion that the decision was taken to remove the seals on top of the shafts. The puddling clay was slowly removed firstly from the upcast shaft, followed by about a half the planking. Vast amounts of highly explosive gases immediately issued forth, so combustible were these gases that they "fired" the Davy lamps up to a distance of ten yards from the shaft. After a while these gases weakened, and work began on the downcast shaft. With the removal of the clay, the first board was taken up and an immense "suck" was observed, an indication that the ventilation was taking its proper course. All seemed well, and it appeared that an exploration party could be arranged to descend the pit within a few hours. About three o'clock Jacob Higson, was looking over the rim of the upcast shaft, and remarked to Thomas Knowles one of the colliery proprietors "That all seemed quiet below, and that within a few hours they should be able to descend". He had scarcely finished the sentence, when he heard a great rush of wind from below, this was followed by a long blast of fire.

The men and officials around the top of the upcast shaft were blow tens of yards on to the nearby railway. Those that could looked up in shock and horror and they saw a dark and dense thick cloud of smoke rise from the other shaft, a split second later vivid red flames filled the shaft and shot thirty yards and more above the headgear. At the this shaft nearly everyone in the vicinity was severely injured, and for at least two of them, their injuries didn't matter for they were killed outright. John Knowles, son of one of the owners of the pit, had a broken leg and other injuries. Mr. Pickard, the miners agent was so badly injured that he had to be helped to his home as he could hardly walk. The fore-man joiner, Farrimond and a man named Peak were injured so severely that they died the same day. Two bodies were recovered from the scaffolding just below the rim of the downcast shaft, and were identified as men named Ashurst, and Walsh. They were described as being terrible mangled, having took the full force of the blast. The reports of the day go into horrific details, and tell that "Some time after the explosion, a limb was found a considerable distance from the shaft which was thought to have belonged to Ashurt".

A good while after, it was realised another man named Shuttleworth was missing. He too was working on the scaffolding, and it was assumed he was caught by the force of the blast and precipitated to the bottom of the shaft. The force of the explosion showed in the headgearing, built from large timbers, which were smashed like matchwood. The hoppet that had been hanging over the shaft, was thrown up and tangled with the remains of the headgear. So loud was the report of the blast that it was heard several miles away, and the flames were seen by many in the borough. Messengers sent out for doctors to attend to the injured, were stopped by people standing at their doorways, who begged for information, fearing that another pit had fired. Again crowds assembled on the Moss pit bank, whose numbers swelled and had to be controlled by police and mine officials in case of another blast. The only option open to them now appeared to be, that of flooding the mine. The work went on into the early hours, the men knocking off about three o'clock. Three constables were left on duty overnight, and shortly before four o'clock noticed that the smoke from the shafts was increasing in quantity, and approached for a better vantage point.

They got within thirty yards when immense sheet of flames shot from the bowels of the mine high into the air, this was followed by a loud blast. The policemen ran for their lives through the fields as debris showered down on them from all directions. The shaking of the ground was felt in villages four and five miles away. A further repetition took place around six o'clock, while not on the same scale, it did set fire to the headgear, and the winding house. The Borough fire engine was called in, but its hoses were far too short to reach and at half past eight the headgear collapsed, the huge cast iron wheels breaking and landing on top of the shaft, but failed to fall down it. A number of minor bursts continued through out the day, though none were as large as the one in the early morning. Work continued in flooding the pit, the reports from down below diminished to "growls" till these too whimpered out, Moss pit wasn't giving up its victims easily. Soon there were five pumps filling the mine with an estimated 50,000 gallons of water per hour. Over the next few weeks this process continued until all the mine workings were filled with water.

Coroners Inquiries were called week after week at the Railway Tavern at Ince, where the colliery proprietors gave a progress report on how the bodies where going to be recovered. This was no easy job, firstly the pit had to be de-watered which was too take many months. In addition there was severe damage to the shafts linings, huge voids caused by the blast and water had to be filled in and made safe. It was to be over twelve months before the remains of the victims started to be recovered, and that's all they were...remains. The intense heat of the fires and explosions reduced the bodies of the victims to mere charred bones. Many of these were found at the foot of the upcast shaft, washed out of the Nine Feet Mine by the water it was presumed. Identification of these was considered impossible, some were able to be identified. Not in the normal sense though, for they were too mutilated even for that. One was identified by his clogs by a witness, for the clogs formerly belonged to him.

Elizabeth Shuttleworth had the harrowing experience of identifying her husband who was killed in the second explosion by a shoe and a piece of shirt. It was getting on for two years after the disaster, before it was considered that all the remains were recovered. The shafts were then sealed, and it is credit to the colliery owners that no expense was spared in recovering the bodies and doing the decent thing. All mining disasters are horrific and the Wigan area at that time was no stranger to them. But surely the Moss Pit disaster must rank among the most disastrous, whilst not in numbers killed but in the events that occurred afterwards. In Ince cemetery, a simple memorial records that disastrous day in September 1871, placed there by Thomas Knowles M.P. New shaft sinking's were made at Moss Colliery, and eventually another four shafts were working. By the late 1940s the colliery was employing nearly 750 men, and was worked by the Wigan Coal Corporation. After Nationalisation, the Coal Board continued the mining until November 1962, when Moss Colliery was eventually abandoned. The events of that fateful September day of 1871 faded away into coal mining history books.

|

|

|

Unity Brook Pit Disaster

Unity Brook colliery was located at Kearsley between the Bolton and Manchester in a south-east direction. There were two shafts at the colliery upcast and downcast in ventilation, though the downcast was the one used for the winding of coal and men. The depth of the shafts was about 360 yards down to the Cannel Seam, the other seam worked at the pit was the Trencherbone, some 60 yards above the Cannel Mine. The workings were stated to be of a small extent which would seem to indicate that these two seams had only just been opened up. From the bottom of the downcast shaft in the Cannel Mine, an inclined roadway was driven to the dip of the seam, which was approx. 1 in 4 away from the shaft.

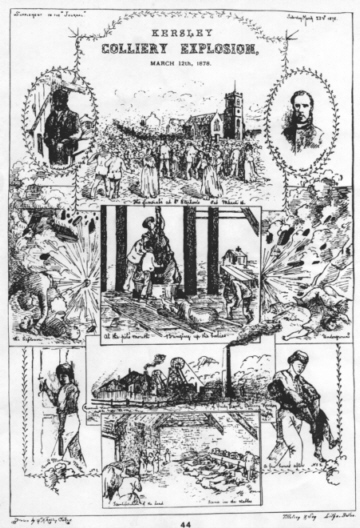

This roadway was known as the Engine Plane Down Brow from here five other roadways on each side were driven to the boundary, the East and the West workings. These in turn were connected at intervals of about 40 yards and various air doors controlled the air currents around the workings of the mine. Open lights were in use at the colliery, that is candles, and indeed were preferred by the miners over the Davy lamp. This was not unusual in this part of the Lancashire Coalfield, the miners at Clifton Hall Colliery seven years after this disaster were still using candles!. This could well be understood, for no gas was ever found at the pit, until September 1877 when the cut-throughs were made at the far end of the workings. Following this however, there were a number of reports of gas at the pit. The early morning of March 12th 1878, started in the usual manner for the colliery underlooker James Holt. He descended the pit to make his preshift examination, at the far end of the West Workings he found a small fall of roof.

This he apparently considered of little importance, and in all other respects the colliery workings were as normal. However, in the course of the morning, he was called back to the area of the roof fall by his assistant William Mayoh. The fall had increased considerably, having come down some 3 or 4 feet in thickness and covering an area of about 10 yards by 7 yards. In addition, the roof was still coming down on the pack walls which had been built to support it. In these circumstances, a man of Holt's experience, and those of the fireman Mayoh, should have immediately forbade the use of naked lamps. As this was the first fall of its type on these West Workings, they either chose to ignore the matter or it never occurred to them. Holt went to the top of the fallen debris where he found a good circulation of air. He then arranged with the fireman Mayoh, and some of the men to set a good strong prop before setting off to his other duties. James Holt finished his work in the Cannel Mine and then went up into the Trencherbone Seam some 60 yards above. Here he spent an hour or two seeing to the workings before making his way to the cage to be wound up about 1 o'clock.

His usual time for making to the pit top would normally be around 3 o'clock, but the colliery manager Isaiah Johnson was away for the day on colliery business, and Holt had to see to the affairs on the surface. He signalled the cage to be brought from the Cannel Mine. When the cage arrived at the Trencherbone Mouthing in the shaft, he found a miner named Ralph Welsby from the east side workings of the Cannel Mine. It was also before Welsby's time for coming up the pit, but he had arranged before hand to leave early to see his sick child. The two men emerged on the pit banking, at exactly 10 minutes past one o'clock, the pit fired. All the men in the Cannel Mine, numbering 42 lost their lives as well as the onsetter at the Trencherbone mouthing. Such was the blast, both shafts were dis-arranged, the shaft lining was ripped out of the upper portion, timbers were broken and steel landing plates were torn up. One of the cages at the downcast shaft was at the top and escaped the greater force of the blast through there being an opening at the bottom of it, the other cage was at the bottom of the Cannel Mine.

The rope to this cage hung in the shaft loose and dis-connected. Hurried arrangements were quickly made, James Holt the underlooker accompanied by two men named Teesdale entered the cage. They descended to within five yards above the Trencherbone Mine, when the cage was stopped by fallen debris. Holt got out of the cage and clinging to the cage guide ropes he climbed down to the Trencherbone mouthing, here he found several men still alive. Joseph Dickinson, the Mines Inspector for the area in response to a telegraph was at the colliery about 3 o'clock, just two hours after the event. By this time a hoppet had replaced the cage in the shaft, some of the debris had been removed and Holt was able to get some men out of the Trencherbone Mine. The air coming up the shaft smelled strongly of afterdamp, but happily no smell of burning which indicated at least that there was no fires below ground. The fresh air was still being drawn down the downcast shaft, though the men being removed smelled strong of the afterdamp and some appeared to be suffering from the effects of the gas. The air going down the shaft to the Trencherbone Mine was soon contaminated with the fumes and afterdamp rising from the Cannel Mine, and there was no sign of life from that seam.

The news spread quickly, soon a number of mining engineers from other local collieries were on the scene to give their assistance, including Edward Pilkington and Simon Horrocks. About 30 men were raised from the Trencherbone Seam as quickly as possible before there was any change in circumstances, in which case all would have been lost. The Mines Inspector Joseph Dickinson and the underlooker Holt descended to the Trencherbone Mine, here the air current appeared to take its normal course, and was downcasting. The two men made a quick search for the missing onsetter, but were unable to find him. They then checked the main air doors were intact and that the ventilation furnace was out, these appeared to be in order. Following this, an attempt was made to descend down to the Cannel Mine but the shaft was blocked solid with timber and other debris. They shouted down through the broken timbers in a vain hope of some reply, none was forthcoming, and they returned to the surface arranging for the pit carpenters to descend and remove the obstructions.

An hour later they returned up the shaft, bringing with them the dead body of the onsetter whom they found in the sump at the bottom of the shaft having been blown there with the blast of the explosion. Holt, Dickinson a Mr. Grimshaw and a Mr. Woodward again descended the shaft, this time they made it to the Cannel Mine. The scene before them was chaotic with broken timbers, mine tubs and roof falls. The air was thick with afterdamp and made the men's eyes water, but enough oxygen was gratefully present to make it breathable. They first tried to move along the upper west level where the fall had occurred earlier that morning, but found the after-damp and fire-damp too much. Leaving this, they went to the engine brow where they found considerable destruction, they then went through the other parts of the mine as quickly as possible. All the men they came across in these workings were already dead.

Their bodies were burnt and some of them were badly injured, nearly all apparently lying where they were struck by the blast. The air doors and screens were all blown away, but they managed to get to all the workings except the upper west levels. Having made sure there was no further life to save, they made their way back towards the shaft about 8 o'clock having explored for some two hours. Arrangements were made to restore the ventilation and remove the rest of the bodies and to protect those doing this work.

By the following day, the upcast shaft was explored and found to be damaged like the downcast, rubble littered the pit shaft bottom which had either fallen or been blown there. All the bodies had been found except for three, which were later found under the debris in the sump hole at the bottom of the shaft. It was now possible to reach the fall on the west level workings, and this now extended for some 25 yards by 20 yards, or seven times the extent it was when Holt left it before the explosion. Fire-damp was still coming off freely, and mixing with the general body of the air, the pit here was coated with dust and near the fall was a deposit of soot. The fall was determined as the centre of the blast, timber, trams, air doors, wood and steel lay scattered around the workings. Twelve months later, when Joseph Dickinson again returned to the pit, gas was still issuing from the explosive point from fresh fissures. Nineteen men and boys from this disaster were laid to rest in the churchyard at St. Stephen's Kearsley, 100 widows and fatherless children were left from this disaster.

The jury recorded the deaths of the deceased was purely accidental and that all possible precautions had been used in the working of the mine. This is in spite of the evidence of Joseph Dickinson inspector of mines statement that if self-extinguishing lamps, like Stephenson's or the Muizer, been in use at the colliery, the gas would in all probability passed off harmlessly, and forty three men and boys over whom so many households are weeping would have been alive now. Or as one writer to the local newspaper condemning the verdict, penned Safety lamps were not used because it was resolved after due deliberation, that money is more precious than human life. The weeping wives and mothers of the time, would I am sure dis-agree. Rather like the proverbial Closing the door after the horse has bolted naked flames were never again used at Unity Brook colliery.

|